Stephen K. Hayes (born September 9, 1949 in Delaware) is a martial arts teacher and author.

Background

Black Belt Hall of Fame member, An-shu Hayes is a noted martial arts author. The nineteen books he has authored have sold over 1.3 million copies and have been translated into five languages. He is a 1971 graduate of Miami University with a Bachelor of Arts degree in theater. He has worked as an actor, notably in the TV miniseries Shogun.[[1]] He is married to Rumiko Urata. The couple has two daughters, Reina and Marissa.

Stephen K. Hayes is considered an authority on ninjutsu and a knowledgeable practitioner of esoteric Tendai mikkyo Buddhism. Today, Mr. Hayes lives and works in Dayton, Ohio, and was once again featured on the cover of Black Belt magazine for their March 2007 issue. The issue contains a chapter from his soon-to-be-released book Ninja Vol 6, Secret Scrolls of the Warrior Sage. The magazine’s opening editorial as well focuses on Mr. Hayes, and describes him as "one of the 10 most influential living martial artists in the world."

Biography

After graduating from Miami University in 1971, he spent time in search of authentic martial traditions, working his way up to sam dan in the Korean martial art of Tang Soo Do (tangsudo). Frustrated with the limitations he'd encountered in his training, he packed his bags and headed for Japan.

In June of 1975, he finally met the teacher he'd been seeking all his life in Grandmaster Masaaki Hatsumi, the founder of Bujinkan Dōjō. Stephen K. Hayes returned to the United States, and with his close friend Bud Malmstrom set off the "ninja boom" of the 1980s, creating one of the largest martial arts phenomena since Bruce Lee. During this time, he helped introduce ninjutsu to America and Western Europe and is responsible for many people becoming aware of ninjutsu. A number of today's senior American Bujinkan practitioners began training with Hayes during this time period, including Bud Malmstrom, Jack Hoban, Mark Davis, Jean-Pierre Seibel, Courtland Elliott, and many more.

In 1991 Hayes also received Tokudo priesthood ordination in Tendai Buddhism from Tendai Master and Vajra Acharya Dr. Clark Jikai Choffy. In 1993, Hayes was awarded the judan (tenth degree black belt) degree from Grandmaster Hatsumi. In 1997, he founded the martial art of To-Shin Do, an art based in his experience of budo taijutsu and life experiences, including security escort work for the Dalai Lama of Tibet. Hayes has also founded a Buddhist Order based on his teachings and experiences with Tibetan Buddhism and Tendai called the Blue Lotus Assembly.

Hayes and his SKH Quest Corporation have continued with their work of making martial arts accessible to people everywhere. The SKH Quest network now spans 18 schools in 12 states.

Affiliation with the Bujinkan

On May 14, 2006, during training in the Bujinkan Hombu Dojo, Soke Masaaki Hatsumi had Steven K. Hayes' name placard taken off the Bujinkan rank board. Without ceremony or fanfare, 12th dan Shidoshi George Ohashi took the name placard down while people were training. Soke Hatsumi stated that Steven K. Hayes was no longer recognized as a judan in the Bujinkan. [2] [3] On May 20, 2006, as a result of the Internet rumors that circulated following these events, Shidoshi Ohashi, also the Bujinkan's administrator, posted the following on the Bujinkan's Hombu & Ayase website: [4] (Archive of [5])

Although the latest news from the Hombu seems to have surprised many people, the facts involved are very simple.

Soke has decided that the person in question has moved away from the Bujinkan and so he is no longer recognized as a Bujinkan member. His name placard has been removed from the 10th dan board in the Hombu Dojo. (Soke doesn't care if people call it a Hamon or not.)

Trivia

During his time in Japan, Hayes occasionally worked as a photographic model. He can be seen in the handbook for the Canon AE1 camera, holding the camera.

He was the stunt double for Richard Chamberlain in the TV miniseries Shogun.

Books by Stephen Hayes

- Ninja combat method: A training overview manual, Beaver Products, 1975.

- Ninja Vol. 1: Spirit of the Shadow Warrior, Ohara Publications, 1980. ISBN 0-89750-073-3

- Ninja Vol. 2: Warrior Ways of Enlightenment, Ohara Publications, 1981. ISBN 0-89750-077-6

- Ninja Vol. 3: Warrior Path of Togakure, Ohara Publications, 1983. ISBN 0-89750-090-3

- Ninja Vol. 4: Legacy of the Night Warrior, Ohara Publications, 1984. ISBN 0-89750-102-0

- Ninja Vol. 5: Lore of the Shinobi Warrior, Ohara Publications, 1989. ISBN 0-89750-123-3

- Ninja Vol. 6: Secret Scrolls of the Warrior Sage. Forthcoming, 2007 - (ISBN-10: 0-89750-165-X) (ISBN-13: 978-0-89750-156-9)

- Wisdom from the Ninja Village of the Cold Moon, Contemporary Books, 1984. ISBN 0-8092-5383-6

- Ninjutsu: The Art of the Invisible WArrior, McGraw-Hill, 1984. ISBN 0-8092-5478-6

- Tulku: A Novel of Modern Ninja, Contemporary Books, 1985. ISBN 0-8092-5332-1

- The Mystic Arts of the Ninja, McGraw-Hill, 1985. ISBN 0-8092-5343-7

- Ninja Realms of Power: Spiritual Roots and Traditions of the Shadow Warrior, Contemporary Books, 1986. ISBN 0-8092-5334-8

- The Ancient Art of Ninja Warfare: Combat, Espionage and Traditions, Contemporary Books, 1988. ISBN 0-8092-5331-3

- The Ninja and Their Secret Fighting Art, Tuttle Publishing, 1990. ISBN 0-8048-1656-5

- Enlightened self-protection: The Kasumi-An ninja art tradition : an original workbook, Nine Gates Press, 1992. ISBN 0-9632473-9-5

- Action Meditation: The Japanese Diamond and Lotus Tradition, Nine Gates Press, 1993. ISBN 0-9632473-7-9

- First steps on the path of light: Tendai-shu Buddhist mind science study guide, self-published, 1997.

- Secrets from the Ninja Grandmaster : Revised and Updated Edition (with Masaaki Hatsumi), Paladin Press, 2003. ISBN 1-58160-375-4

- How to Own the World: A Code for Taking the Path of the Spiritual Explorer, self-published, 2006. ISBN 0-9632473-2-8

- Enlightened Warrior Gyo-ja Practitioner Recitation Handbook for Daily Practice, self-published, 2006

External links

Ninja

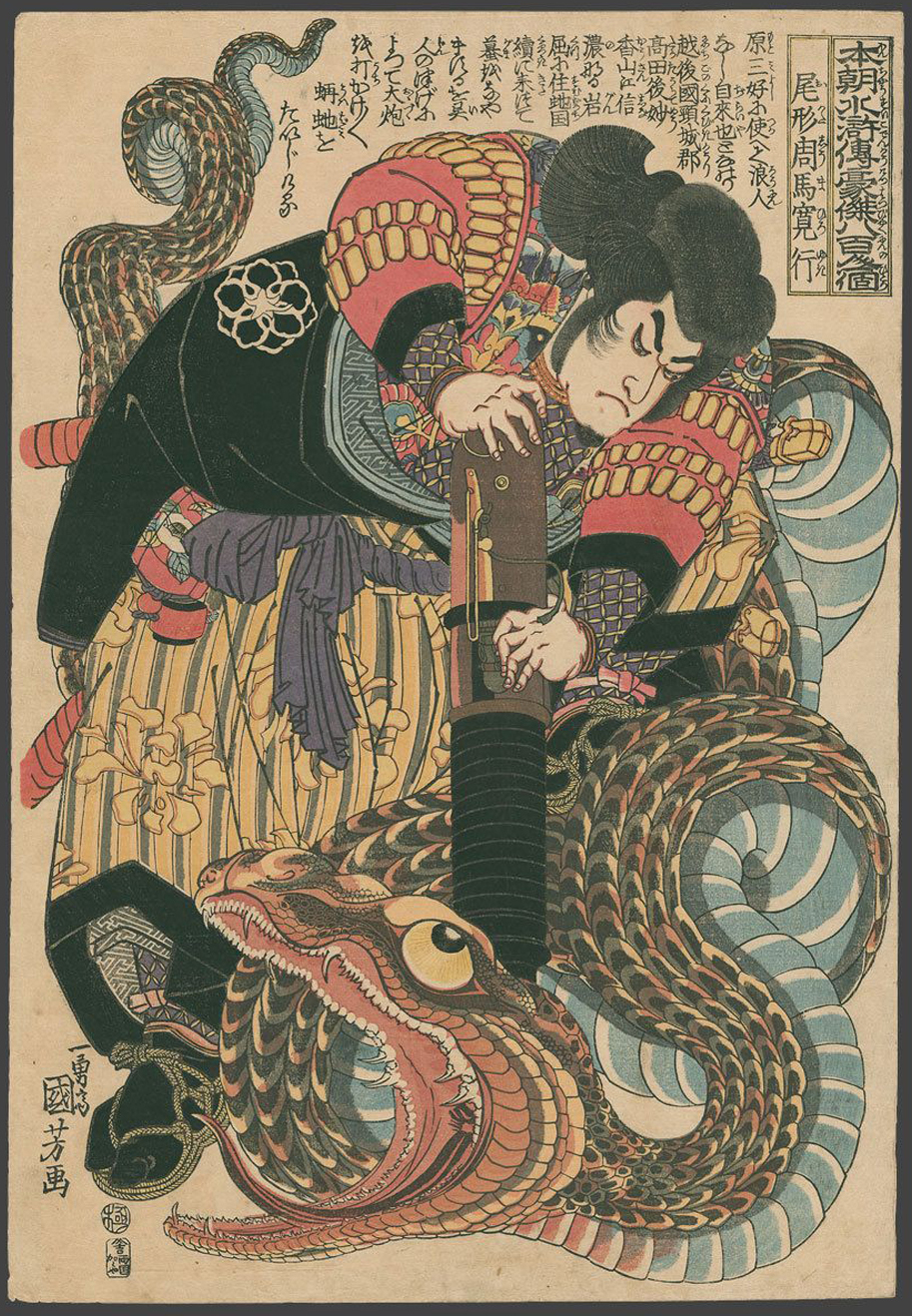

Jiraiya, ninja and title character of the Japanese folktale Jiraiya Goketsu Monogatari.

A ninja may have been an assassin or spy in Japanese culture, usually trained for stealth. Appearing in fourteenth century feudal Japan, and active from the Kamakura to the Edo period, their roles may have included sabotage, espionage, scouting, and assassination missions, perhaps in the service of feudal rulers (daimyo or shogun). Since the art of stealth killing leaves no witness, the truth about the ninja will likely remain hidden.

Etymology

Ninja is the on'yomi reading of the two kanji 忍者 used to write shinobi-no-mono (忍の者), and Oniwaban (お庭番) both of which are native Japanese words for people who practice ninjutsu (sometimes transliterated as ninjitsu 忍術). Ninja and shinobi-no-mono, along with shinobi, another variant, became popular in the post-World War II culture. The term 志能備, has been traced as far back as Japan's Asuka period (538-710 AD), when Prince Shotoku is alleged to have employed one of his retainers as a ninja.[citation needed] The underlying connotation of shinobi (忍, pronounced nin in Sino-Japanese compounds) is "to do quietly" or "to do so as not to be perceived by others" and—by extension—"to forebear," hence its association with stealth and invisibility. Mono (者, likewise pronounced sha or ja) means "thing" and/or "person." The nin of ninjutsu is the same as that in ninja, whereas jutsu (術) means skill or art, so ninjutsu means "the skill of going unperceived" or "the art of stealth"; hence, ninja and shinobi-no-mono (as well as shinobi) may be translated as "one skilled in the art of stealth." Similarly, the pre-war word ninjutsu-zukai means "one who uses the art of remaining unperceived."

Historical period of origin

The ninjas' use of guerilla tactics against better-armed enemy samurai does not mean that they were limited to espionage and undercover work; that is simply where their actions most notably differed from the more accepted tactics of samurai. Their weapons and tactics were partially derived from the need to conceal or defend themselves quickly from Samurai, which can be seen from the similarities between many of their weapons and various sickles and threshing tools used at the time. [1].

Ninja as a group first began to be written about in 15th century feudal Japan as martial organizations predominately in the regions of Iga and Koga of central Japan, though the practice of guerilla warfare and undercover espionage operations goes back much further.

At this time, the conflicts between the clans of daimyo that controlled small regions of land had established guerilla warfare and assassination as a valuable alternative to frontal assault. Since Bushido, the Samurai Code, forbade such tactics as dishonorable, a daimyo could not expect his own troops to perform the tasks required; thus, he had to buy or broker the assistance of ninja to perform selective strikes, espionage, assassination, and infiltration of enemy strongholds (Turnbull 2003).

There are a few people and groups of people regarded as having been potential historical ninja from approximately the same time period. It is rumored that some of the higher-ranking daimyos and shoguns were in fact ninja, and exploited their role as ninja-hunters to deflect suspicion and obscure their participation in the 'dishonorable' ninja methods and training.

Though typically classified as assassins, many of the ninja were warriors in all senses. In Hayes's book, Mystic Arts of the Ninja, Hattori Hanzo, one of the most well-known ninja, is depicted in armor similar to that of a Samurai. Hayes also says that those who ended up recording the history of the ninja were typically those within positions of power in the military dictatorships, and that students of history should realize that the history of the ninja was kept by observers writing about their activities as seen from the outside.

“Ninjutsu did not come into being as a specific well defined art in the first place, and many centuries passed before ninjutsu was established as an independent system of knowledge in its own right. Ninjutsu developed as a highly illegal counter culture to the ruling Samurai elite, and for this reason alone, the origins of the art were shrouded by centuries of mystery, concealment, and deliberate confusion of history” The Historical Ninja. –By Soke Masaaki Hatsumi

A similar account is given by 10th Dan instructor Stephan K. Hayes – “The predecessors of Japan's’ ninja were so called rebels favoring Buddhism who fled into the mountains near Kyoto as early as the 7th century A.D. to escape religious persecution and death at the hands of imperial forces” Ninjutsu: The Art of Invisibility.

Historical organization

In their history, ninja groups were small and structured around families and villages, later developing a more martial hierarchy that was able to mesh more closely with that of samurai and the daimyo. These certain Ninjutsu trained groups were set in these Villages for protection against raiders and robbers.

While ninja are often depicted as male, and nearly all military and related professions were typically limited exclusively to males, "ninja museums" in Japan declare women to have been ninja as well (Turnbull 2003). A female ninja may be called kunoichi; the characters are derived from the strokes that make up the kanji for woman. They were sometimes depicted as spies who learned the secrets of an enemy by seduction; though it's just as likely they were employed as household servants, putting them in a position to overhear potentially valuable information. In either case, there is no historical support for the modern image of female ninja assassins and warriors, they more likely had roles as spies and couriers, similar to male ninja.

As a martial organization, ninja would have had many rules, and keeping secret the ninja's clan and the daimyo who gave them their orders would have been one of the most important ones.

For modern hierarchy in ninjutsu, see: Ninjutsu

Historical garb, technique, and image

There is no evidence that historical ninja limited themselves to all-black suits. In modern times, camoflage based upon dark colors such as dark red and dark blue, and give better concealment at night. Some ninja may have worn the same armor or clothing as samurai or Japanese peasants.

The stereotypical ninja that continually wears easily identifiable black outfits (shinobi shozoku) comes from the Kabuki theater. [2] Prop handlers would dress in black and move prop around on the stage. The audience would obviously see the prop handlers but would pretend they were invisible. Building on that willing suspension of disbelief, ninja characters also came to be portrayed in the theater as wearing similar all-black suits. This either implied to the audience that the ninja were also invisible, or simply made the audience unable to tell a ninja character from the many prop handlers until the ninja character distinguished himself from the other stagehands with a scripted attack or assassination.

Ninja boots (jika-tabi), like much of the rest of Japanese footwear from the time, have a split-toe design that improves gripping and wall/rope climbing. They are soft enough to be virtually silent.

The actual head covering suggested by sōke Masaaki Hatsumi (in his book The Way of the Ninja: Secret Techniques) utilizes what is referred to as Sanjaku-tenugui, (three-foot cloths). It involves the tying of two three-foot cloths around the head in such a way as to make the mask flexible in configuration but securely bound. Some wear a long robe, most of the time dark blue (紺色) for stealth.

Associated equipment

The assassination, espionage, and infiltration tasks of the ninja led to the development of specialized technology in concealable weapons and infiltration tools.

Tools

Ninja are said to have made use of weapons that could be easily concealed or disguised as common tools such as the bo and handclaws (shuko, neko-te tekagi) probably being the most famous examples of concealable tools, as well as shuriken (throwing stars), which have more recently been popularized by comic books and movies. Kunai (originally a gardening tool) were also a popular weapon according to some accounts, as they could be hidden easily or carried if the ninja was disguised as a gardener. It was the equivalent of a utility knife, often used to pry or cut rather than fight. The makibishi (tetsu-bishi), a type of caltrop made of iron spikes, is also famous. It could be thrown on the ground to injure a pursuer's feet or thrown out on an enemy's escape path so that the targets could be cut down or shot down with bows and arrows while they looked for another escape route, but it could also be covered with poison.

Ninja are associated with the katana, a long, curved sword that is usually associated with the samurai. In popular culture, ninja are often shown as using special short swords called ninja-ken (or ninja-tō, see below for explanation), or "shinobigatana" (Note the inclusion of the term shinobi, a synonym for ninja). Ninja-ken are shorter than a katana but longer than a wakizashi. The ninja-to was often more of a utilitarian tool than a weapon, not having the complex heat treatment of a usual weapon[citation needed]. Another version of the ninja sword was the shikoro ken (saw sword). The shikoro ken was said to be used to gain entry into wooden buildings, and could also have a double use by cutting (or slashing in this case) opponents.

While the nunchaku are often associated with ninja in the contemporary western imagination, historic ninja use of the weapon is unlikely on anachronistic grounds. However, most historians believe that ninja may have adapted a rice-threshing flail into a weapon for similar use.

One non-offensive tool used by ninja is irogome (literally, "colored rice"). Irogome was uncooked rice seeds colored in five or six different colors: red, black, white, yellow, blue, and sometimes brown. They would be placed on the ground or handed from ninja to ninja. Each combination carried certain meanings like "all clear" or "an enemy check point is ahead".

Specialized weapons and tactics

Ninja also employed a variety of weapons and tricks using gunpowder. Smoke bombs and firecrackers were widely used to aid an escape or create a diversion for an attack. They used timed fuses to delay explosions. Ōzutsu (cannons) they constructed could be used to launch fiery sparks as well as projectiles at a target. Small "bombs" called metsubushi (目潰し, "eye closers") were filled with sand and sometimes metal dust. This sand would be carried in bamboo segments or in hollowed eggs and thrown at someone, the shell would crack, and the assailant would be blinded. Even land mines were constructed that used a mechanical fuse or a lit, oil-soaked string. Secrets of making desirable mixes of gunpowder were strictly guarded in many ninja clans.

Other forms of trickery were said to be used for escaping and combat. Ashiaro are wooden pads attached to the ninja's tabi (thick socks with a separate "toe" for bigger toe; used with sandals). The ashiaro would be carved to look like an animal's paw, or a child's foot, allowing the ninja to leave tracks that most likely would not be tracked.

Also a small ring worn on a ninja's finger called a shobo would be used for hand-to-hand combat. The shobo (or as known in many styles of ninjutsu, the shabo) would have a small notch of wood used to hit assailant's pressure points for sharp pain, sometimes causing temporary paralysis. A suntetsu is very similar to a shobo. It could be a small oval shaped piece of wood affixed to the finger by a small strap. The suntetsu would be held against a finger (mostly middle) on the palm-side and when the hand that was thrust at an opponent, the longer piece of wood would be used to hit the pressure points.

In Popular Culture

Ninja appear in both Japanese and Western fiction. Depictions range from realistic to the fantastically exaggerated.

In the mid-1960s the Japanese TV series The Samurai created a major wave of popularity for the ninja in Japan, and this was replicated in several other countries where the series was screened, most notably in Australia, where the program's popularity rivaled its following in Japan among children.

Many sources, including books, television, movies, and websites are portraying ninjas in non-factual ways, often for humor or entertainment. A popular example is the Real Ultimate Power website and book, which are satirically written, feigning obsessive over-enthusiasm for ninja.

Modern Para-military groups

- Armed groups active under Indonesian rule in East Timor, which terrorized populations supporting independence and were allegedly controlled by the Indonesian military, in some cases called themselves "Ninja." However, there seems little resemblance between their methods and those of Japanese ninja, and the name seems to have been borrowed from films and books rather than being directly influenced by the Japanese model.

- The Angolan Special Police Forces, are a are a specialized para-military police force officially referred to as the “emergency police” but popularly known as “Ninjas” [1] [2].

Notes

- ^ Angola: Peace Monitor, II, 9, 5/29/'96. UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA - AFRICAN STUDIES CENTER. Retrieved on 2007 March 23.

- ^ Democracy Fact File: Angola. sardc.net. Retrieved on 2007 March 23.

References

- Hatsumi, Masaaki (June 1981). Ninjutsu: History and Tradition. Unique Publications. ISBN 0-86568-027-2.

- Turnbull, Stephen (February 2003). Ninja AD 1460-1650. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-525-2.

External links

Note: A shobo is a weapon used by the ninja of Japan for striking pressure points on an opponent. It was a piece of wood that was gripped by the wielder and was hung by a ring.

Sparky thinks we're seeing an alias of Bill Murray (who's obviously a dangerous man).

No comments:

Post a Comment